5. Expansion and the Beginning of the Middle Ages

| Key Dates # |

|

|---|

| 431 | Council of Ephesus - Re-affirmation of belief in Jesus as one person

|

| 451 | Council of Chalcedon - Jesus Christ is two natures (Christianity divided for the next 200 years over this matter)

|

| 461 | Death of Patrick

|

| Death of Leo the Great

|

| 480 | Birth of Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy

|

| Birth of Benedict of Nursia

|

| 496 | Conversion of Clovis, king of the Franks

|

| 521 | Birth of Columba, Irish missionary to Scotland

|

| 529 | Council of Orange - upheld Augustine in relation to original sin and grace

|

| 590 | Birth of Gregory the Great (the first official "Pope")

|

| 560 | Birth of Isidore of Seville; his "Three Book of Sentences" is the key theological work until the 12th century

|

| 596 | Augustine is sent from Rome to evangelise Britain

|

| 602 | Lombards convert from Arianism to orthodoxy

|

| 622 | Mohammed's flight ("hijra") from Mecca to Medina, the official birth of Islam

|

| 675 | Birth of John of Damascus, an Eastern Orthodox mystic

|

| 680 | Birth of Boniface, who brought the Gospel to Germany

|

| 711 | Islam reaches Spain

|

| 726-787 | Controversy over the worship of images (icons)

|

| 732 | Battle of Tours halts the spread of Islam from Iberia into France and the rest of Europe

|

| 787 | Council of Nicaea confirms the decision of John of Damascus regarding icons; ongoing controversy in the West

|

| 800 | Charlemagne crowned head of the Holy Roman Empire

|

Overview

During the fifth century (and beyond) Christianity continued to grow rapidly.

An earlier sentiment (from a letter written by Cyprian to Donatus in the 3rd Century) continued

to reflect the impact of Christianity on the known world:

"It is a bad world, Donatus, an incredibly bad world. But I have discovered in the midst of it a

quiet and good people who have learned the great secret of life. They have found a joy and

wisdom which is a thousand times better than any of the pleasures of our sinful life. They are

despised and persecuted, but they care not. They are masters of their souls. They have overcome

the world. These people, Donatus, are Christians. . . and I am one of them."

Much of the appeal of Christianity was the way it helped the poor and needy (there were no

pensions or dole to support the aged or those without work or support), ministered to the sick,

reached out to the suffering during epidemics (Christians became known for their work during

epidemics such as plague, smallpox, measles, when thousands died and others fled for their

lives; pagan religions usually offered little consolation or support), taught love, compassion,

acceptance and equality before God.

Christian preaching, belief in life after death (including as consolation for poor quality of life for

now), forgiveness of sins (a powerful incentive in an age where gods normally resorted to

punishment rather than forgiveness), the Fatherhood of God, inclusive family of God, eternal

rewards for godly living, the return of Christ, all gave hope and security found nowhere else.

The Christian community provided a strong network. Feasts and other commemorations gave

structure and order for new converts.

Rodney Stark's book, The Rise of Christianity, argues that one of the main reasons for the

success of early Christianity was the Christian emphasis on caring for the sick. During the late

Roman period there was a number of devastating plagues: the Antonine Plague (165-180 AD), the

Plague of Cyprian (251-270 AD), and the Plague of Justinian (541-542 AD). These periods

coincided with some of the most prolific growth of Christianity. Stark contends that Christian

communities would have had better survival rates during plagues because of the health care

they provided for one another. Christians also cared for the sick in non-Christian communities,

which would increase the likelihood of their conversion, especially in times of death and

uncertainty. The old pagan religions offered no explanation for why these epidemics were

occurring; Christianity acted as a salvation.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, the imperial court continued to operate

from Ravenna (in the East). This led to increasing debate between the Eastern rulers (the

Patriarch of Constantinople adopted the title Ecumenical Patriarch, which Pope Gregory

opposed) and the popes regarding where the true church was located and who was in charge.

Historians often date the ascension of Gregory as Pope (in 590) as the beginning of the Middle

Ages #. Roman influence continued however. Church (canon) law was based on old Roman law.

Latin became the principle language used by the church. Church hierarchy, architecture,

education and literature reflected Roman styles. Gregory took the title "Vicar of Christ on

Earth" (ie in His place on earth, with His authority in the Church) and "Servant of servants",

titles popes continue to use to this day. Gregory promoted the concept of purgatory.

# We will not be using the popular alternative, "Dark Ages", because this would be at odds with the reality that the

genuine church continued to grow, the light of the Gospel continued, mission work did not cease and humanity moved

forward.

This period is marked by the Christianisation of much of Western Europe.

Controversies

1. Church Hierarchy

During the first centuries of Christianity no central organisation was formed. Each group of

believers was autonomous, but related to other churches. As we have already seen, this led to a

concentration of ecclesiastical (from "ekklesia", or called out, meaning the church, but

increasingly used to describe the formal church) power in the West in Rome. With Gregory (the

"Great") the Bishop of Rome took the title Pope.

The Papacy - From Papa, or Father, the Pope is formally known in Roman Catholic tradition as to

Bishop of Rome, the most important bishop in the Catholic world.

2. Doctrine

Purgatory - prayer for the dead began to emerge in Christian circles in the 2nd century and

intensified over subsequent centuries. This practice was linked to teaching that, after physical

death, (with the exception of martyrs - sound familiar?) the souls of Christians needed additional

cleansing before they were ready for paradise. The Bible does not teach purgatory or prayer for

the dead.

Adoration of Mary - The New Testament affirms the special role that Mary, the mother of Jesus,

played in the incarnation, life and ministry of Jesus Christ:

"And Mary said: "My soul glorifies the Lord and my spirit rejoices in God my Saviour, for he has

been mindful of the humble state of his servant. From now on all generations will call me

blessed, for the Mighty One has done great things for meó holy is his name." (Luke 1:46-49).

Christian acknowledges Mary as a chosen vessel of God. However, the Catholic Church has, in its

own words, "clarified her position and nature through Sacred Tradition." In 431 Mary was

designed as the "Mother of God". From 600 the church has taught that it is permissible for

Christians to offer prayers to Mary. Since that time Mary has been called Queen of the Apostles,

Mother of the Church, sinless (among other titles). These attributions come from some church

traditions, but are at odds with what the Bible teaches.

Iconoclasm

Emperor Leo III attacked the use of images. John of Damascus (676-749) defended the use of

icons in worship by differentiating between veneration and worship. He argued that the use of

icons is an affirmation of Christ's humanity, because a real person can be depicted. Those who

opposed the practice argued that images of Christ are not valid because they can only represent

his humanity, but not his divinity. This response missed the bigger issue of the short step

between an image and idolatry. In 787 the Council of Nicea supported John of Damascus, but

controversy continued.

Mary as "Theotokos"

Gregory "the Great"

3. Council of Ephesus

As we have seen, the Council of Ephesus was held in 431 AD, under orders from the Roman

Emperor Theodosius II. The Council sought broad confirmation of acceptance of the Nicene

Creed and condemned the teachings of Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople from 428-431, in

particular in relation to the role of Mary.

Nestorius argued that Mary be titled the Christotokos, or "Birth Giver of Christ"; the majority of

the Council argued for Theotokos, "Birth Giver of God". (Nestorius did not accept the concept of

Jesus having both human and divine natures in one.) The sermons and teachings of Nestorius

were subsequently ordered to be burned. One result of the Council was increased division

between the Western and Eastern branches of Christianity (not resolved until 1994).

4. Council of Orange

Earlier in this course, we mentioned Augustine of Hippo and the Pelagians. Augustine, who

believed in the doctrine of original sin and the need for divine intervention to bring about

change, opposed Pelagius, who taught that people are born in "state of innocence", that human

nature is basically good, and that people could keep God's word and requirements (without the

need for grace). The Council of Orange (529AD) was an outgrowth of this controversy and

emphasised both human responsibility and the role of the grace of God in bringing about

salvation. The Council upheld Augustine's views.

Nestorian Missionary Enterprises

The Assyrian Church of the East was known as a missionary movement. Early Nestorians fled

persecution in the Christian Roman Empire and settled in Sassanid Persia, where they affiliated

with the local Christian community and became known collectively as the Church of the East.

They subsequently evangelised as far afield as China (Nestorians were in Mongolia at the time of

Ghengis Khan), Siberia, Afghanistan, Japan and India. Not only did they spread the Christian

gospel and plant churches but they also developed written languages for many cultures they

encountered. Over subsequent centuries Nestorian communities were overtaken by Islam and

Buddhism and followers were further persecuted by the Mongols, Kurds and Turks.

Today there are pockets of Nestorians in Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Kuwait, Greece, Italy,

Sweden, Russia, USA, Canada and Australia.

Some Influential Christians During the Fifth to Eighth Centuries

Patrick, Missionary to Ireland (387-460)

Born Maewyn Succat, a Roman, son of Christians, Patrick was kidnapped as a teenager by Irish

slave traders and taken to work as a shepherd in Ireland. After meeting local Christians, he was

converted to Christ. After managing to escape, he spent a period in a monastery in Europe

before going back to Ireland in 432 as a missionary/bishop. Patrick travelled throughout Ireland,

preaching, teaching and baptizing converts. Patrick was a committed church planter and

evangelist. He established many churches, schools and monasteries. He influenced Irish kings

and strove for the abolition of slavery. "Patron Saint" of Ireland since the 7th Century.

"In the light, therefore, of our faith in the Trinity I must make this choice: regardless of

the danger, I must make known the gift of God and everlasting consolation. Without fear

and frankly I must spread everywhere the name of God so that after my decease I may

leave a bequest to my brethren and sons whom I have baptised in the Lord - so many

thousands of people."

Clovis (466-511)

Clovis was a pagan chief who united the Franks under a single monarchy. He became a Christian

and the first such to rule Gaul. Clovis was baptised a catholic, which ensured Catholic

ascendancy over the Arians in Gaul. He made Paris his capital and Christian centre.

Benedict of Nursia (480-550)

Born into a noble Roman family, Benedict was converted to Christianity. He established a

monastic order at Montecassino and (between 535 and 540) developed a "rule" to govern its

operation. With Gregory's mandate, the rule developed into the Benedictine Order. The rule,

spread slowly in Italy and Gaul. It provided instructions for the government and spiritual and

material well-being of monasteries by initiating the role of "Abbot" (from Greek abba =

"father") and integrating obedience, prayer, manual labour, and study into a disciplined daily

routine. The images we have of a monastery in action reflect Benedictine models. By the time

of Charlemagne the Benedictine Rule had replaced most other monastic practices in Europe.

Columba (521-597)

Columba grew up in a Christian environment in Donegal, Ireland. He was instrumental in

planting Christian communities in Ireland before relocating to Scotland, where he continued his

evangelistic outreach to Druid Scots and Picts. Missionaries from Ireland increasingly targeted

unevangelised parts of Europe, including Gaul and northern Europe.

Augustine

At the end of the 6th century most English were pagans; by the end of the 7th they were

notionally Christians (some kingdoms occasionally relapsed into paganism in the early decades).

In 596 AD, 40 monks set out from Rome to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons. (England had previously

been part of the Roman Empire.) Leading the group was Augustine, the prior of their monastery

in Rome, whose attention had been drawn to Angle boys on sale as slaves in Rome. During his

journey, Augustine heard about the ferocity of the Anglo-Saxons and returned to Rome; after

being assured that their fears were groundless, the team returned to pursue the work. Their

efforts commenced in the area of Kent, ruled by Ethelbert, a pagan king married to a Christian

named Bertha. In 597 Ethelbert was baptized (Augustine baptism by immersion). Augustine did

not always meet with success; his attempts to reconcile Anglo-Saxon Christians (who adopted

Christianity through earlier mission outreach, by Celtic Christians) with the original Briton

Christians (driven into western England by Anglo-Saxons) ended in failure. Conversion was a topdown

process: people followed rulers. Augustine achieved success eventually. The Britons

refused to give up certain Celtic customs at variance with the church. Rather than destroy

pagan temples and customs, he allowed pagan rites and festivals to be retro-fitted as Christian

feasts. His work produced considerable fruit over time, leading to the notional conversion of

England. He has been called Augustine of Canterbury and the "Apostle of England."

Isidore of Seville (560-636)

Born in Cartagena, educated in Seville. Archbishop of Seville for 30+ years. Instrumental in

bringing together opposing forces in the Visigoth conflict over Arianism. One of the most learned

Christian leaders. Campaigned for conversion of the Visigothic Arians in Spain to Catholicism.

Venerable Bede (673-735)

St Bede (as he is commonly known) was born in Durham, England and grew up in the care of

Benedictine monks. He is possibly the greatest of Anglo-Saxon scholars. During his life he wrote

more than forty books on theology and history, especially the history of Christianity in England.

He is credited with the concept of dating BC and AD.

Boniface (675-754)

Boniface was born in Wessex, England. A Benedictine monk with experience in mission in

Ireland, England and the region now known as the Netherlands, he brought Christianity to

Germany. Boniface had a strong influence on Pepin the father of Charlemagne and was

instrumental in spreading Christianity in the Frankish Empire in the 700s. He cut down an oak

tree dedicated to the Germanic god Thor at Geismar and built a church out of it. Boniface was

killed by band of pagan Frisians as he was reading the Scriptures to a group of new Christians on

Pentecost Sunday in 754. He is known as the Apostle of Germany and is recognised as the

"Patron Saint of Germany" today. Some traditions credit him with introducing the Christmas

tree.

The Rise of Islam

Mohammed was born in Mecca in the year 570 as a member of the Quarish tribe, which claimed

descent from Abraham's son Ishmael (see Genesis 16). He worked as a trader, frequently

meeting Jews and Christians (including Nestorians) on his travels and observing internecine

struggles in the early church. At the age of 25 he married a wealthy 40 year-old widow named

Khadija. He had numerous wives and one child, a daughter named Fatima. From the age of 40,

Mohammed began to claim revelations, or "recitations" (lit. Qur'an) about God from "the

Archangel Gabriel". His message called for rejection of the prevailing crude polytheism, in the

face of judgment to come.

He was initially opposed by the majority of Meccans. Persecuted because of his dogmatism,

Mohammed fled with his followers to the city of Medina in 622. This flight, or "hijra", marked

the beginning of the Muslim calendar. Nine years later, when his forces were strong enough, he

defeated Mecca, smashed most of its idols and established Islam as the official religion.

After his death in 632, the Muslim community was divided. Bitter arguments over succession led

to a major split, with the majority (Sunnis) following the elected Caliphs and a smaller group

(Shi'ites) supporting claims by his descendants. Islam has been divided ever since.

Other denominations include the Allawites (a heretical branch of Shi'ism, based mainly in Syria),

Sufis (a mystical branch), Druze (followers of an Egyptian sect, in the Lebanese and Israeli

mountains, Druze communities are exclusive, claim "secret" knowledge and believe in

reincarnation), Wahabis (very strict; they control Saudi Arabia) and the Ahamadiya sect (Syria).

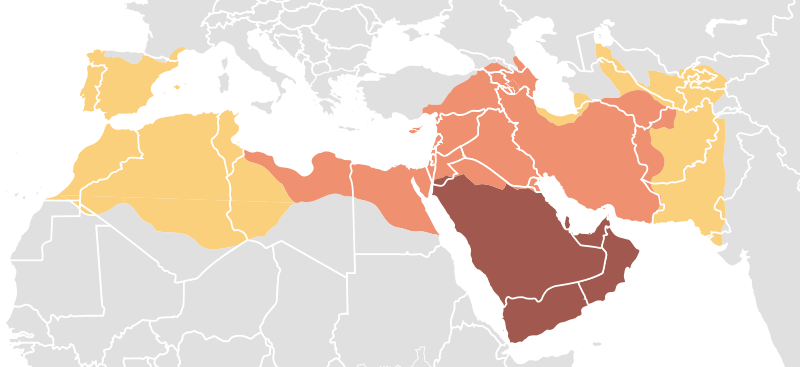

Within a hundred years of Mohammed's death, Islam spread beyond the Middle East and

conquered an area larger than the Roman Empire. Dynasties shifted from Mecca to Damascus,

then Baghdad. Some Christian communities in the Middle East accepted the arrival of Islam,

because it freed them from Byzantine rule. Some theologians believe that elements of Jewish

and Christian teaching in Islam made the new religion attractive, and enabled it to be accepted

as part of God's plan.

Pressure was exerted on Christians and pagans to convert to Islam. In North Africa, following the

Arab-Muslim invasion, Christians were permitted to exercise their religion, on payment of a tax

and agreement not to proselytize. Around 720 additional pressure was exerted by Caliph Omar II

on Christian Berbers to convert to Islam. By rapid conversion or a process of attrition, Islam

succeeded in weakening the Church in North Africa, leading to its disappearance.

The Arab Muslim invasion of North Africa, which began around 643, was completed by the

capture of Carthage in 698 and Ceuta in 709. In 711 Muslim armies stormed the Iberian

Peninsula at Gibraltar (Jabal Tarik, named after Tarik Ibn Ziyad, the Moorish leader of the

invading army) and gradually conquered almost the entire peninsula. An Umayyad Caliphate was

established, based around city of Cordoba (Qurtuba), north of Seville. The Great Mosque of

Cordoba, which started out as a Visigothic church (Saint Vincent) in 600AD was the centre of the

Caliphate; it was converted back to a church in the 14th century.

The advance of Islam was in France in the Battle of Tours (or Battle of Poitiers in 732), when

Frankish armies under Charles Martel defeated Emir Abdul Rahman Al Ghafiqi Abd al Rahman

near the city of Tours. Muslim forces occupied Spain until 1492, when the last stronghold,

Granada, fell to the Catholic Kings Ferdinand and Isabella. Many Muslims today continue to

lament the loss of Spain to global Islam.

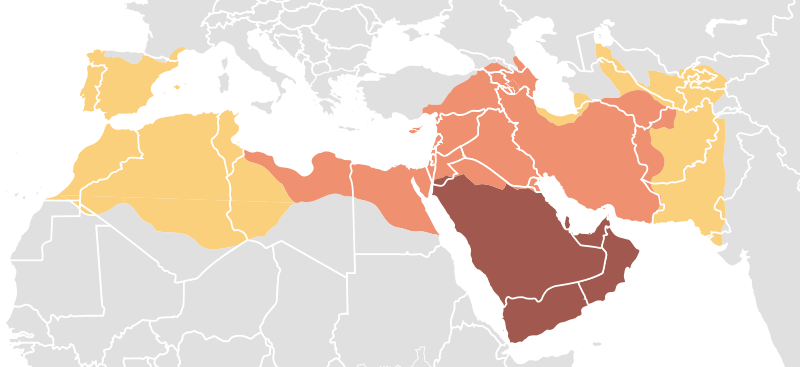

Expansion under Mohammad, 622-632

Expansion during the Patriarchal Caliphate, 632-661

Expansion during the Umayyad Caliphate, 661-750

Beginning and Consolidation of the Holy Roman Empire

We now enter the first stages of a new era in church and theological history, the so-called Middle

Ages. Between the 4th and 7th centuries waves of conquering tribes rise and fell. The Vandals,

Huns, Visigoths, Burgundians and others were gradually subsumed. Politically, much of Europe

increasingly was incorporated in a political construct that came to be known as the Holy Roman

Empire (in an attempt to restore some of the glory of the old Roman Empire, but with Christian

branding). The Papacy and Frankish rulers increasingly worked together and provided military

assurances for Rome, which was vulnerable to attack from the Lombards. On Christmas Day 800

in St Peter's, Rome, Charlemagne (Charles the Great or Charles I, King of the Franks from 768),

who finally defeated the Lombards, was crowned Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire in Rome.

Charlemagne imposed the Benedictine Rule in monasteries all over Europe.

Christianity now dominated politics, culture and life in Europe. Cities were dominated by

cathedral churches. A Christian art emerged (using old figures and techniques, but with new

messages). Christian poets continued the classical tradition, but were now centred on the

Gospel. Celibate men were accorded increasing power. Martyrs and saints became the new

super-heroes. A new morality pervaded society; secular law reflected Christianity. The church

was triumphant and dominant as late antiquity finished and a new age began.

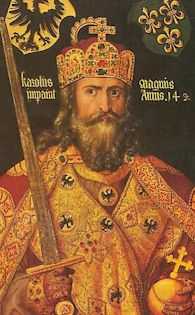

Charlemagne and Empire

Issues Facing Christians During this period

- power was increasingly centred in Rome, shared later with the Holy Roman Emperor, but

also balanced with centrist thinking in the eastern part of the empire

- Christianity shaped political thinking, but the reverse also applied

- the Christian community was becoming increasingly diversified

- Christian community was becoming more about external power structures than the kind

of relationship with God and one another that the New Testament and the Gospel teach;

more about cultural, linguistic and economic identity than discipleship, the inner life,

fellowship of believers

- those who sought discipleship did so in increasing isolation, eg as hermits, monks, mystics

- tradition (and current thinking and interpretation) had equal weight to the Scriptures;

theology was subsumed and made subservient to social interests and priorities

- Islamic expansion in the margins increasingly posed a threat that would ultimately lead to

clashes of tectonic proportions, the results of which are still being felt today.